L1: OLED Displays

Table of Contents

- OLED displays

- The Adafruit GFX Library

- Let’s make stuff!

- Resources

- Next Lesson

Video. Playing Pong on the Adafruit monochrome 1.3” 128x64 pixel OLED display with the Parallax 2-axis joystick and tactile buttons. The source code for Pong is here. Parts of this video are sped up 4x.

In this lesson, you will learn about organic light-emitting diode (OLED) displays, basic graphics programming, and a brief introduction to two serial communication protocols called I2C (Inter-Integrated Circuit) and SPI (Serial Peripheral Interface)

OLED displays

Organic light-emitting diode (OLED) displays are relatively new technology, increasingly used in TVs, computer monitors, smartphones, and handheld game consoles. Unlike LCDs, which require backlighting, each OLED pixel generates its own light providing superior contrast and color control.

In this lesson, we will be using the monochrome (black-and-white) OLED displays from Adafruit along with their display control and graphics libraries. To do so, we need to install some libraries.

Install Arduino libraries

To use the Adafruit OLED display, we need two libraries:

- The Adafruit_SSD1306 display driver library, which handles display communication, memory mapping, and low-level drawing routines

- The Adafruit_GFX graphics library, which provides core graphics routines for all Adafruit displays like drawing points, lines, circles.

Fortunately, the Arduino IDE makes library installation easy. We can do it right from the IDE itself. Follow our step-by-step installation guide here.

Wiring the Adafruit OLED display

Once you’ve installed the requisite libraries, you’re ready to wire up the display!

The SSD1306 driver chip and accompanying library provides two different communication methods—each require different wirings: I2C (Inter-Integrated Circuit) and SPI (Serial Peripheral Interface). The default is I2C, which is what we will use in this lesson. For more on the SPI mode, see Adafruit’s official docs.

While the OLED display requires a 3.3V power supply and 3.3V logic levels for communication, the Adafruit breakout board includes a 3.3V regulator and level shifting on all pins, so you can interface with either 3V or 5V devices. Additionally, recall that the I2C requires pull-up resistors on the clock (SCL) and data (SDA) lines so that both are pulled-up to logic level HIGH by default. Thankfully, the Adafruit breakout board also includes these resistors. So, the wiring is quite straightforward, consisting of only four wires!

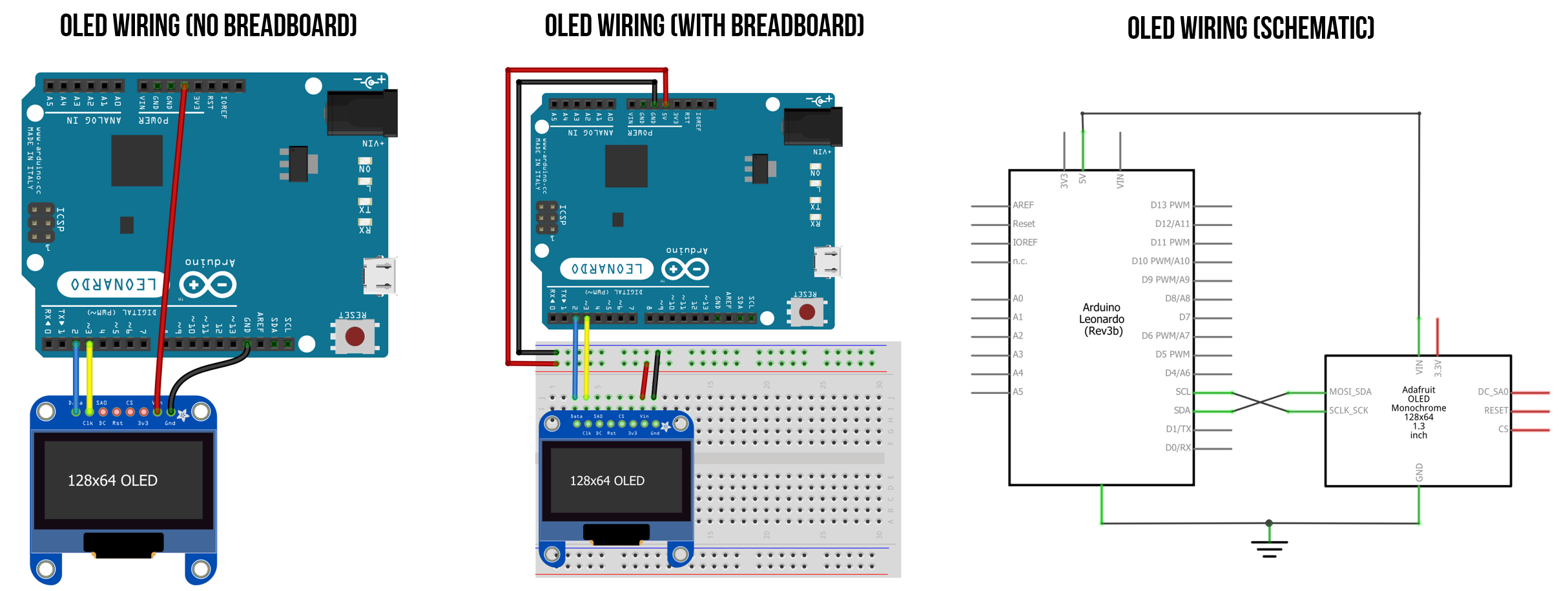

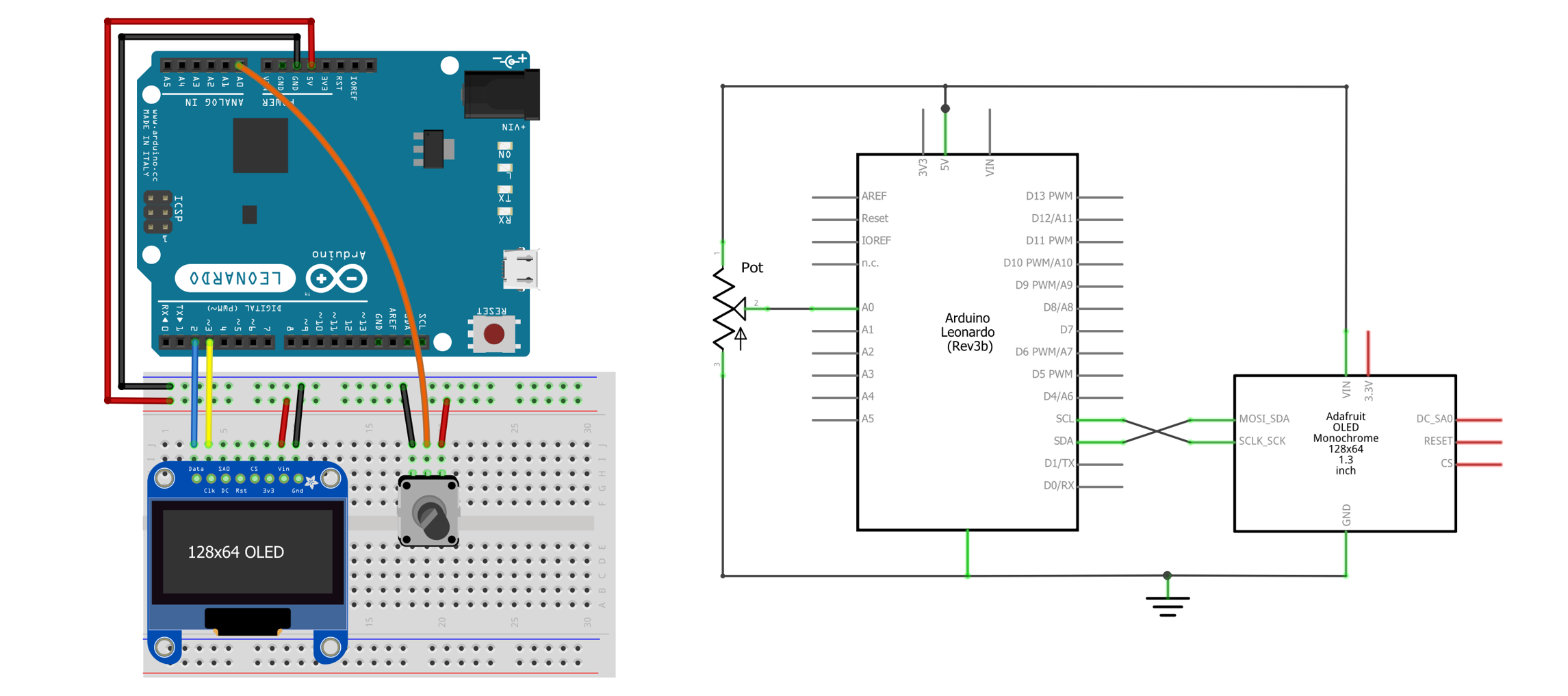

The wiring diagram and circuit schematic are below. We used the Qwiic color-coding system for our wires: blue for data (SDA), yellow for clock (SCL), black for ground (GND), and red for the voltage supply (5V). The I2C pins differ depending on your board. For example, on the Arduino Uno, they are A4 (SDA) and A5 (SCL) rather than digital pins 2 (SDA) and 3 (SCL) as they are on the Leonardo.

Figure Wiring the Adafruit OLED display requires only four wires (and nothing else). I used the standard STEMMA QT color coding for my wires: blue for data (SDA), yellow for clock (SCL), black for ground (GND), and red for the voltage supply (5V). Note that the I2C pins differ depending on your board. For example, on the Arduino Uno, they are A4 (SDA) and A5 (SCL) rather than digital pins 2 (SDA) and 3 (SCL) as they are for the Leonardo.

Figure Wiring the Adafruit OLED display requires only four wires (and nothing else). I used the standard STEMMA QT color coding for my wires: blue for data (SDA), yellow for clock (SCL), black for ground (GND), and red for the voltage supply (5V). Note that the I2C pins differ depending on your board. For example, on the Arduino Uno, they are A4 (SDA) and A5 (SCL) rather than digital pins 2 (SDA) and 3 (SCL) as they are for the Leonardo.

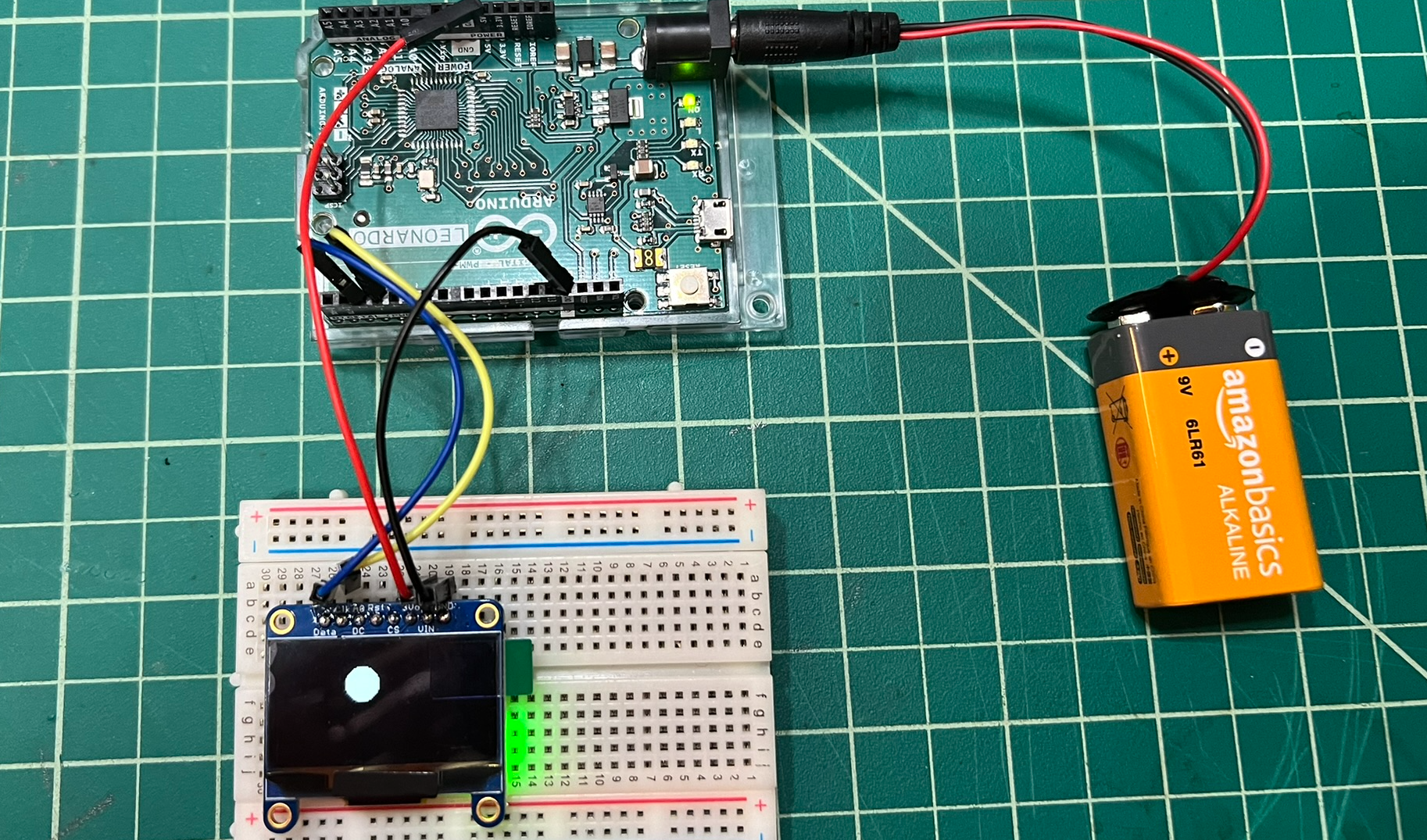

Physical wiring with jumper cables

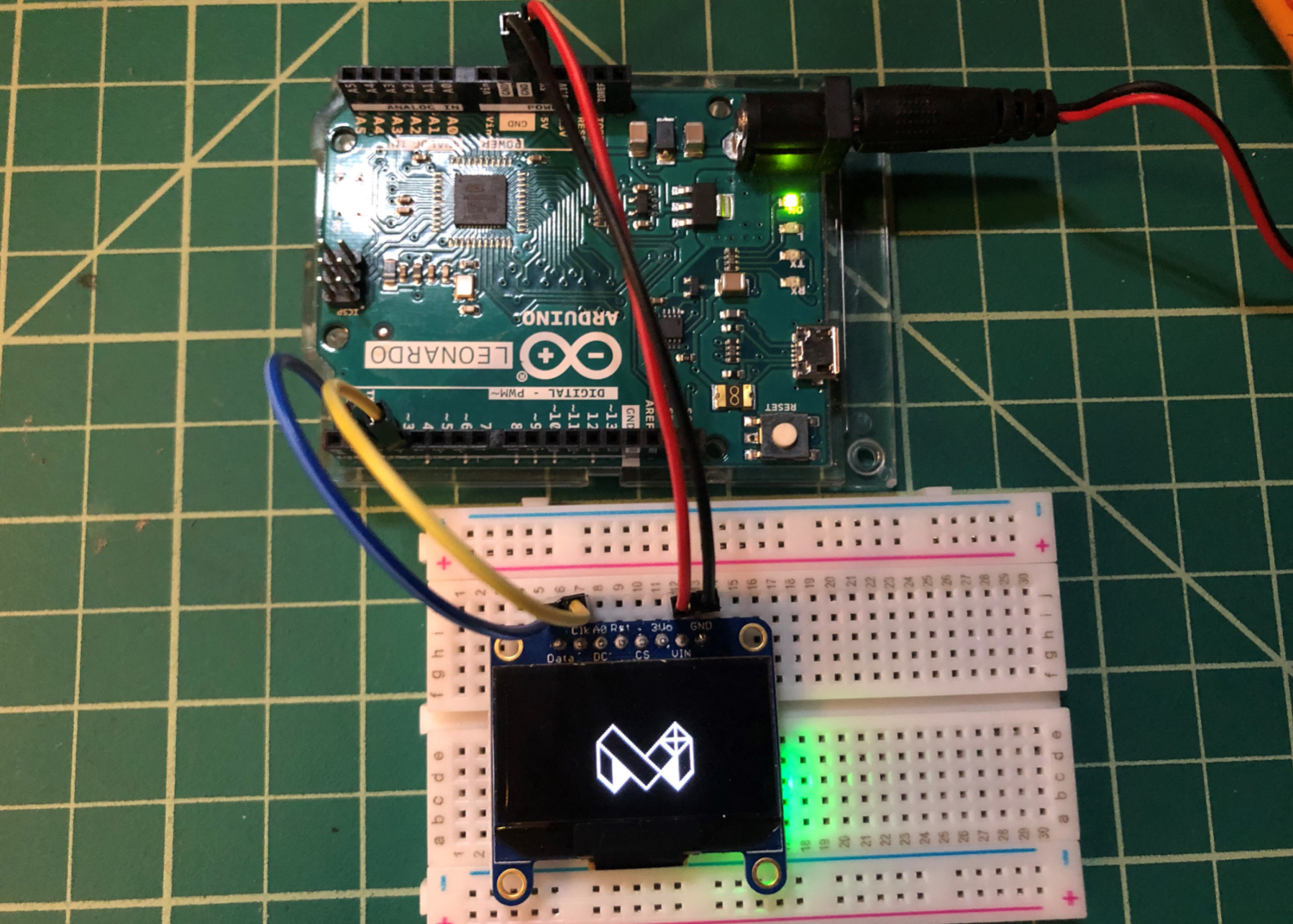

Here’s a picture of actually wiring up the OLED using jumper cables.

Figure Physically wiring the OLED display with jumper cables. The Arduino is running this demo code ‘BitmapBounce.ino’

Figure Physically wiring the OLED display with jumper cables. The Arduino is running this demo code ‘BitmapBounce.ino’

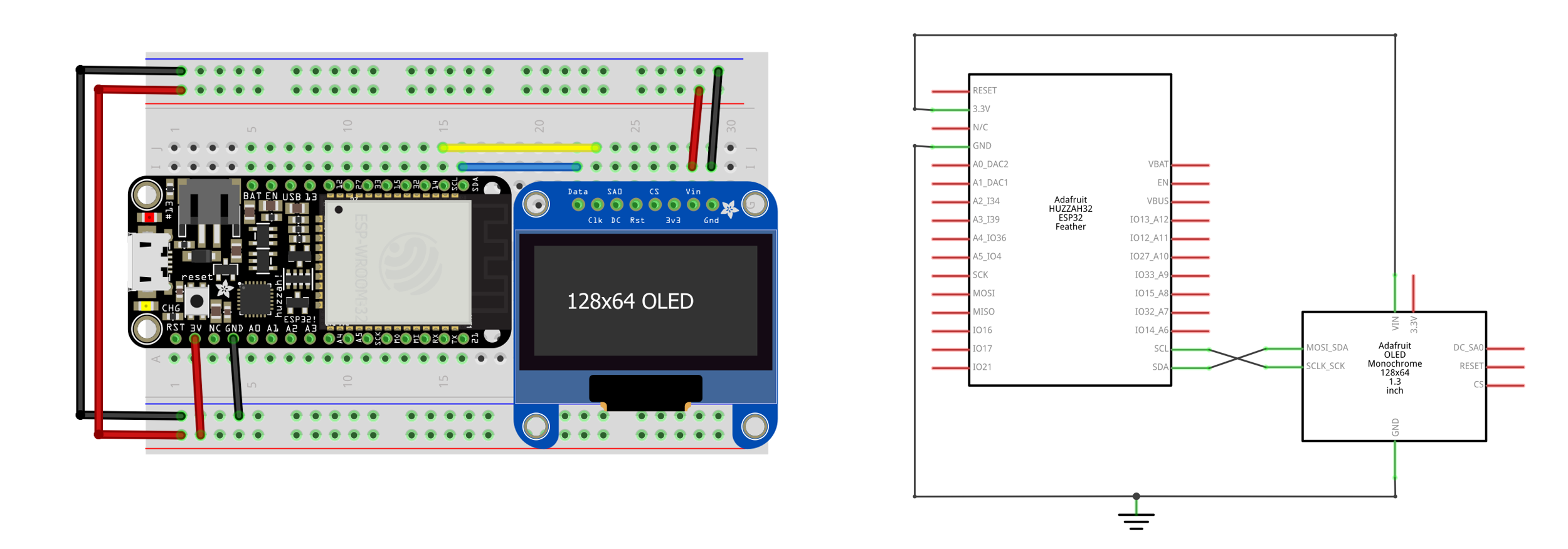

ESP32 wiring

Some students have asked for the ESP32 wiring, so here it is. The ESP32 board runs at 3.3V vs. the 5V supplied by the Arduino Leonardo and Uno; however, the OLED itself only needs 3V for operation. You can learn more about the ESP32 here.

Figure. Wiring diagram for the Adafruit Huzzah32 ESP32 board with OLED.

Figure. Wiring diagram for the Adafruit Huzzah32 ESP32 board with OLED.

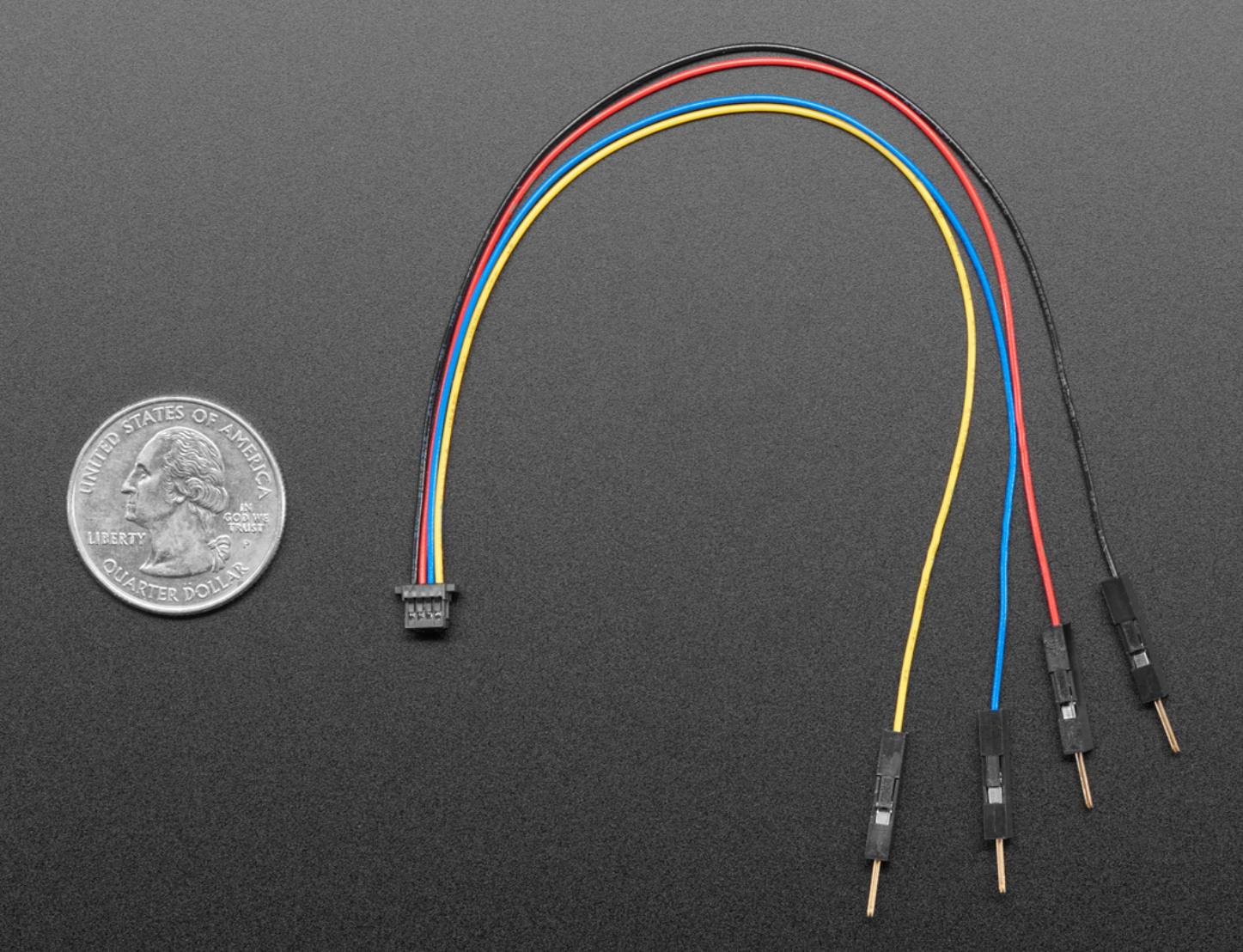

STEMMA QT wiring

Starting in ~2017, many Adafruit and SparkFun breakout boards began including standardized connectors to more easily connect multiple electronic devices without soldering or working with lots of individual wires. This is particularly helpful because I2C let’s us daisy chain I2C-compatible devices together. The Sparkfun connection standard for I2C devices, called Qwicc, was later adopted by Adafruit, which they call STEMMA QT.

Both Sparkfun and Adafruit sell a variety of Qwiic/STEMMA QT cables, including this female-to-female version (for ~$0.95) and this female-to-male jumper cable version ($0.95). You can use the female-to-female cable to daisy chain multiple devices together.

| STEMMA QT / Qwiic Female-to-Female Cable | STEMMA QT / Qwiic Female-to-Male Jumper Cable |

|---|---|

|  |

The video below shows the OLED display hooked up to a STEMMA QT female-to-male jumper cable:

Video Running the demo ssd1306_128x64_i2c with a STEMMA QT cable.

Testing the OLED display

Once you’ve wired the OLED display, we’re ready to test it with some code!

We will run one of the examples that ships with the Adafruit_SSD1306 library called ssd1306_128x64_i2c. This example iterates through a variety of drawing demonstrations, including: drawing lines, outlining and filling rectangles, circles, rounded rectangles, and triangles, rendering text with different styles, and drawing and animating bitmaps. You can view the example source code here.

To open and run the example, follow these steps.

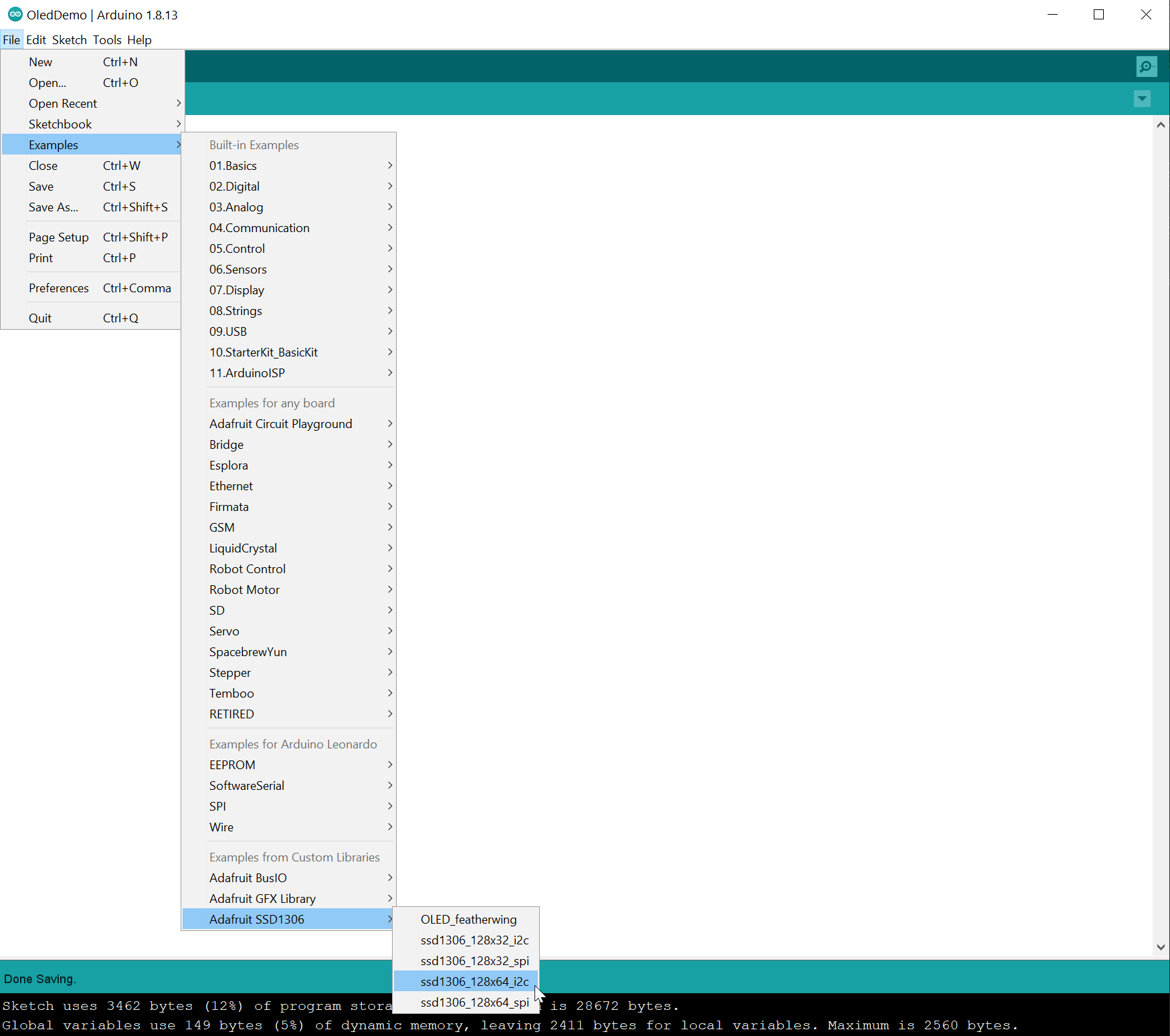

Step 1: Open the example

In the Arduino IDE, go to File -> Examples -> Adafruit SSD1306 and select ssd1306_128x64_i2c. You might have to scroll down in the Examples file menu to see it.

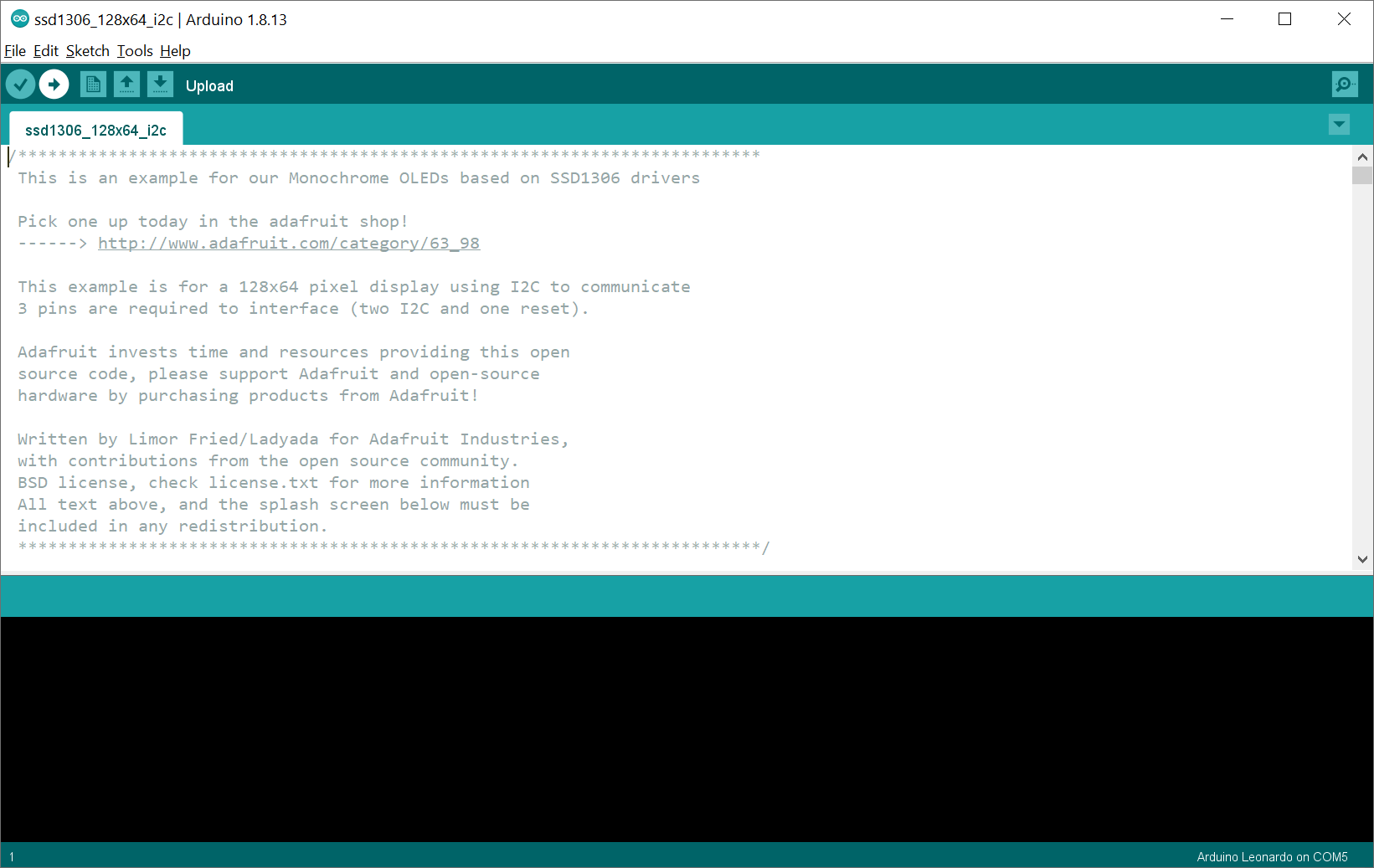

Step 2: Compile and upload the example

Now, compile and upload the example.

Step 3: Watch the demo

Once the code has compiled and uploaded, it should look something like this:

Video Running the demo ssd1306_128x64_i2c. Parts of this video are sped up 4x.

If you’re curious how they rendered something, please do look over the source code. There is nothing magic here and reading the code may help inform your future prototypes!

The Adafruit GFX Library

Now that we’ve got our OLED display wired up correctly and tested that it’s working, let’s talk about how to draw to the screen.

To provide a common API for drawing across all Adafruit LCD and OLED displays, Adafruit created a general-purpose graphics rendering library, called Adafruit GFX. Put simply, rather than having to individually turn on/off OLEDs in the OLED matrix—which would be tedious (though perhaps a useful learning exercise)—the Adafruit GFX library provides higher level drawing routines to do this for you, like drawing rectangles, circles, text, and bitmaps.

Though we highly recommend them, you certainly do not have to use the Adafruit SSD1306 and GFX libraries to use OLED displays. There are many tutorials online that describe how to directly interface with the SSD1306 OLED driver and create drawing routines. For example, this “Getting Started With OLED Displays” by JayconSystems on Instructables. Remember, the Adafruit engineers simply built their libraries to make it easier to program OLEDs… and we’re thankful! But you could also follow the SSD1306 and I2C specs and build your own libraries!

Coordinate system and pixels

If you’re familiar with graphics APIs in other programming frameworks—like C#’s System.Drawing library, Processing’s Java drawing library, p5js’ JavaScript drawing library, etc.—the Adafruit GFX library works much the same (at a high level).

The black-and-white OLED consists of a matrix of OLEDS, called pixels, which can be individually addressed to turn on/off (or, in the case of colored displays, to control individual RGB OLEDs to create colors). As with all other drawing libraries, the coordinate system for these pixels places the origin (0,0) at the top-left corner with the x-axis increasing to the right and the y-axis increasing down.

![]() Figure An overview of the 128x64 matrix of LEDs—we call each LED a “pixel”. We’ve found that students sometimes flip the y-axis in their minds. So, make sure to note how the origin starts at

Figure An overview of the 128x64 matrix of LEDs—we call each LED a “pixel”. We’ve found that students sometimes flip the y-axis in their minds. So, make sure to note how the origin starts at (0,0) and the x-axis increases to the right and the y-axis increases down. Image created in PowerPoint and uses images from Fritzing and the Adafruit GFX tutorial.

Thus, to turn “on” the LED at pixel (18, 6) using Adafruit GFX, we would write: drawPixel(18, 6, SSD1306_WHITE). For black-and-white displays, the last argument can be either SSD1306_WHITE to draw a white pixel or SSD1306_BLACK to draw a black pixel (these parameters are defined in Adafruit_SSD1306.h). For color displays, you can instead pass in an unsigned 16-bit value representing RGB colors (see docs).

Drawing subsystem

Below, we describe how to draw shapes, text, and bitmaps. Importantly, when you call any of the drawing routines—from drawLine to drawTriangle—you are not drawing directly to the OLED display. Instead, you are drawing to an offscreen buffer handled by the SSD1306 driver. So, after you call your drawing routines, you must then call the void Adafruit_SSD1306::display() function to push the data from RAM to the display. We’ll show how to do this step-by-step in our examples below.

Figure. Let’s begin by drawing a simple circle at

Figure. Let’s begin by drawing a simple circle at x,y location of 50,20 with a radius of 10. This code is also in GitHub as DrawCircle.ino); however, that code is slightly different in that it centers the circle in the middle of the screen.

Let’s begin by drawing a circle at x,y location of 50,20 with a radius of 10. We’ll start first with pseudo code to understand the drawing pipeline then actual C++.

// One-time initialization

Adafruit_SSD1306 _disp = new Display(); // Create new SSD1306 display object

_disp.begin(SSD1306_SWITCHCAPVCC, 0x3D); // Allocate RAM for image buffer, set VCC, and address

// Drawing

_disp.clearDisplay(); // Set all pixels to off

_disp.fillCircle(50, 20, 10, SSD1306_WHITE); // Draw to offscreen buffer

_disp.display(); // Render offscreen buffer to display

And here’s the actual C++ implementation (the full code is on GitHub as DrawCircle.ino).

// Instantiate SSD1306 driver display object

Adafruit_SSD1306 _display(SCREEN_WIDTH, SCREEN_HEIGHT, &Wire, OLED_RESET);

void setup(){

Serial.begin(9600);

// Initialize the display using begin()

// The first parameter is the VCC selection. Typically, pass SSD1306_SWITCHCAPVCC.

// The second is the address of the display for i2c. Even if you have the display configured

// for SPI (which doesn't use addresses), you still need to pass a param here (can be 0)

if (!_display.begin(SSD1306_SWITCHCAPVCC, 0x3D)) { // Address 0x3D for 128x64

Serial.println(F("SSD1306 allocation failed"));

for (;;); // Don't proceed, loop forever

}

}

void loop(){

// Clear the display

_display.clearDisplay();

// Put in drawing routines

// In this case, draw a circle at x,y location of 50,20 with a radius of 10

_display.fillCircle(50, 20, 10, SSD1306_WHITE);

// Render graphics buffer to screen

_display.display();

}Now, because we are drawing the exact same thing on every loop() call, we could just as well put this drawing code into setup() and have it draw once and only once (the graphic content will persist).

// Instantiate SSD1306 driver display object

Adafruit_SSD1306 _display(SCREEN_WIDTH, SCREEN_HEIGHT, &Wire, OLED_RESET);

void setup(){

Serial.begin(9600);

// Initialize the display. If it fails, print failure to Serial

// and enter an infinite loop

if (!_display.begin(SSD1306_SWITCHCAPVCC, 0x3D)) { // Address 0x3D for 128x64

Serial.println(F("SSD1306 allocation failed"));

for (;;); // Don't proceed, loop forever

}

// Clear the display

_display.clearDisplay();

// Draw a circle at x,y location of 50,20 with a radius of 10

_display.fillCircle(50, 20, 10, SSD1306_WHITE);

// Render graphics buffer to screen

_display.display();

}

void loop(){

// Empty on purpose to make a point about how graphic content persists

// on screen

}However, for practical purposes, we always want to put our drawing methods in loop() because we want to support dynamic graphics, which are animated (e.g., graphics that change over time) and/or responsive (e.g., graphics that change in response to input).

Important Reminder

You need to call

_display.display()in order to render the graphics buffer to the screen. It’s not sufficient to simply calldrawCircle,fillRect,drawBitmapas those functions “draw” to an offscreen buffer. Indeed, if you look at the Adafruit_SSD1306.cpp source (available online in GitHub), you’ll see that the functionvoid Adafruit_SSD1306::display(void)“pushes data currently in RAM to the SSD1306 display.”

Drawing shapes

The Adafruit GFX library current supports drawing lines, rectangles, circles, rounded rectangles, and triangles. For all shapes, you can draw an outlined version (e.g., drawRect) or a filled version (e.g., fillRect). The images below are drawn from the Adafruit GFX tutorial.

| Shape and API call | Output |

|---|---|

Linesvoid drawLine(uint16_t x0, uint16_t y0, uint16_t x1, uint16_t y1, uint16_t color); |  drawLine(5, 10, 3, 19, SSD1306_WHITE) |

Rectanglesvoid drawRect(uint16_t x0, uint16_t y0, uint16_t w, uint16_t h, uint16_t color); void fillRect(uint16_t x0, uint16_t y0, uint16_t w, uint16_t h, uint16_t color); |  drawRect(3, 2, 13, 10, SSD1306_WHITE) |

Circlesvoid drawCircle(uint16_t x0, uint16_t y0, uint16_t r, uint16_t color); void fillCircle(uint16_t x0, uint16_t y0, uint16_t r, uint16_t color); |  drawCircle(14, 8, 7, SSD1306_WHITE) |

Rounded Rectanglesvoid drawRoundRect(uint16_t x0, uint16_t y0, uint16_t w, uint16_t h, uint16_t radius, uint16_t color); void fillRoundRect(uint16_t x0, uint16_t y0, uint16_t w, uint16_t h, uint16_t radius, uint16_t color); |  drawRoundRect(3, 1, 17, 12, 5, SSD1306_WHITE) |

Trianglesvoid drawTriangle(uint16_t x0, uint16_t y0, uint16_t x1, uint16_t y1, uint16_t x2, uint16_t y2, uint16_t color); void fillTriangle(uint16_t x0, uint16_t y0, uint16_t x1, uint16_t y1, uint16_t x2, uint16_t y2, uint16_t color); |  drawTriangle(6, 13, 9, 2, 18, 9, SSD1306_WHITE) |

Drawing custom shapes

You can, of course, create custom shapes either by cleverly combining shape primitives (e.g., a rectangle and a triangle to make a basic house) or by implementing your own drawing algorithm and calling drawPixel. The drawPixel API looks like:

| Shape and API call | Output |

|---|---|

Pixelsvoid drawPixel(uint16_t x, uint16_t y, uint16_t color); |  drawPixel(0, 0, SSD1306_WHITE) drawPixel(18, 6, SSD1306_WHITE) drawPixel(6, 13, SSD1306_WHITE) |

Optimized vertical and horizontal line drawing

If you are drawing purely vertical or horizontal lines, then you can use optimized line-drawing functions that avoid angular calculations. For example, we use drawFastVLine in our analog graphing demos below.

For more information and examples, see the Basic Drawing section of Last Minute Engineer’s OLED display tutorial.

Drawing text

There are two methods to render text: drawing a single character with drawChar and using the print rendering subsystem, which mimics the familiar Serial.print() functionality covered in our Intro to Arduino series here.

Method 1: drawChar

To draw a single character, you specify a (x, y) location, the character, the foreground and background color, and a size. By default, characters are 5x8 pixels but an optional size parameter (the last argument) can be passed to scale the font (e.g., a size of 2 will render 10x16 pixels per character).

| Text API call | Output |

|---|---|

Charvoid drawChar(uint16_t x, uint16_t y, char c, uint16_t color, uint16_t bg, uint8_t size); |  drawChar(3, 4, 'A', SSD1306_WHITE, SSD1306_BLACK, 1) |

Method 2: Print rendering

The more common and feature-rich method to draw text is via the print subsystem. Interestingly, the Adafruit_GFX class actually extends the Print class from the Arduino core library. You can view the Serial.print() docs here; the API is the same for the OLED.

Rather than call Serial.print("Hello World"), however, with the OLED display and Adafruit GFX library, you would call _display.print("Hello World"). Here, _display is the Adafruit_SSD1306 object.

To use the OLED’s print functionality, you can first set optional parameters such as the text color, size, and wrapping:

void setTextColor(uint16_t color);

void setTextColor(uint16_t color, uint16_t backgroundcolor);

void setTextSize(uint8_t size);

void setTextWrap(boolean w);Then, to position the text, you set the print cursor with:

void setCursor(uint16_t x0, uint16_t y0);Finally, to print the text at that cursor position, you can call any of the standard Serial.print methods, including this subset:

size_t print(const String &);

size_t print(const char[]);

size_t print(char);

size_t println(const String &s);

size_t println(const char[]);

size_t println(char);See the Serial.print() docs or the Print.h library for more on the print API or read on for an example.

Centering text

In creative coding, visualization, and game dev, we often want to center or otherwise align text. To do so, we need to measure it. Fortunately, the Adafruit GFX library has a method called getTextBounds that does just that!

/**************************************************************************/

/*!

@brief Helper to determine size of a string with current font/size.

Pass string and a cursor position, returns upper-left corner and width and height

@param str The ASCII string to measure

@param x The current cursor X

@param y The current cursor Y

@param x1 The boundary X coordinate, returned by function

@param y1 The boundary Y coordinate, returned by function

@param w The boundary width, returned by function

@param h The boundary height, returned by function

*/

/**************************************************************************/

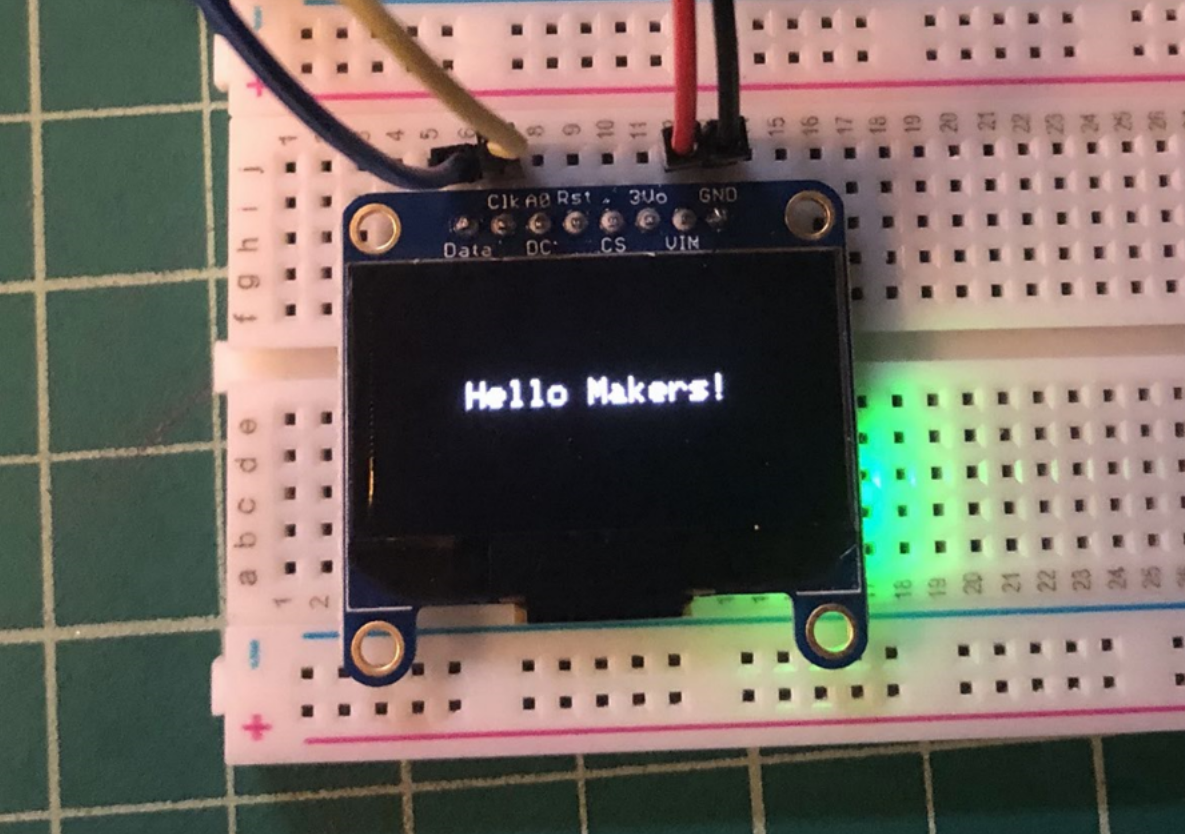

void getTextBounds(String &str, int16_t x, int16_t y, int16_t *x1, int16_t *y1, uint16_t *w, uint16_t *h);For example, in our HelloWorld.ino example, we center the text “Hello Makers!” both vertically and horizontally on the OLED screen. The key excerpt is here:

int16_t x, y;

uint16_t textWidth, textHeight;

const char strHello[] = "Hello Makers!";

// Setup text rendering parameters

_display.setTextSize(1);

_display.setTextColor(WHITE, BLACK);

// Measure the text with those parameters. Pass x, y, textWidth, and textHeight

// by reference so that they are set within the function itself.

_display.getTextBounds(strHello, 0, 0, &x, &y, &textWidth, &textHeight);

// Center the text on the display (both horizontally and vertically)

_display.setCursor(_display.width() / 2 - textWidth / 2, _display.height() / 2 - textHeight / 2);

// Print out the string

_display.print(strHello);

// Render the graphics buffer to screen

_display.display(); Inverting text

We can also invert the text simply by switching the colors in setTextColor(uint16_t color, uint16_t backgroundcolor). So, to draw black text on a white background, we would write _display.setTextColor(BLACK, WHITE);

| setTextColor(WHITE, BLACK) | setTextColor(BLACK, WHITE) |

|---|---|

|  |

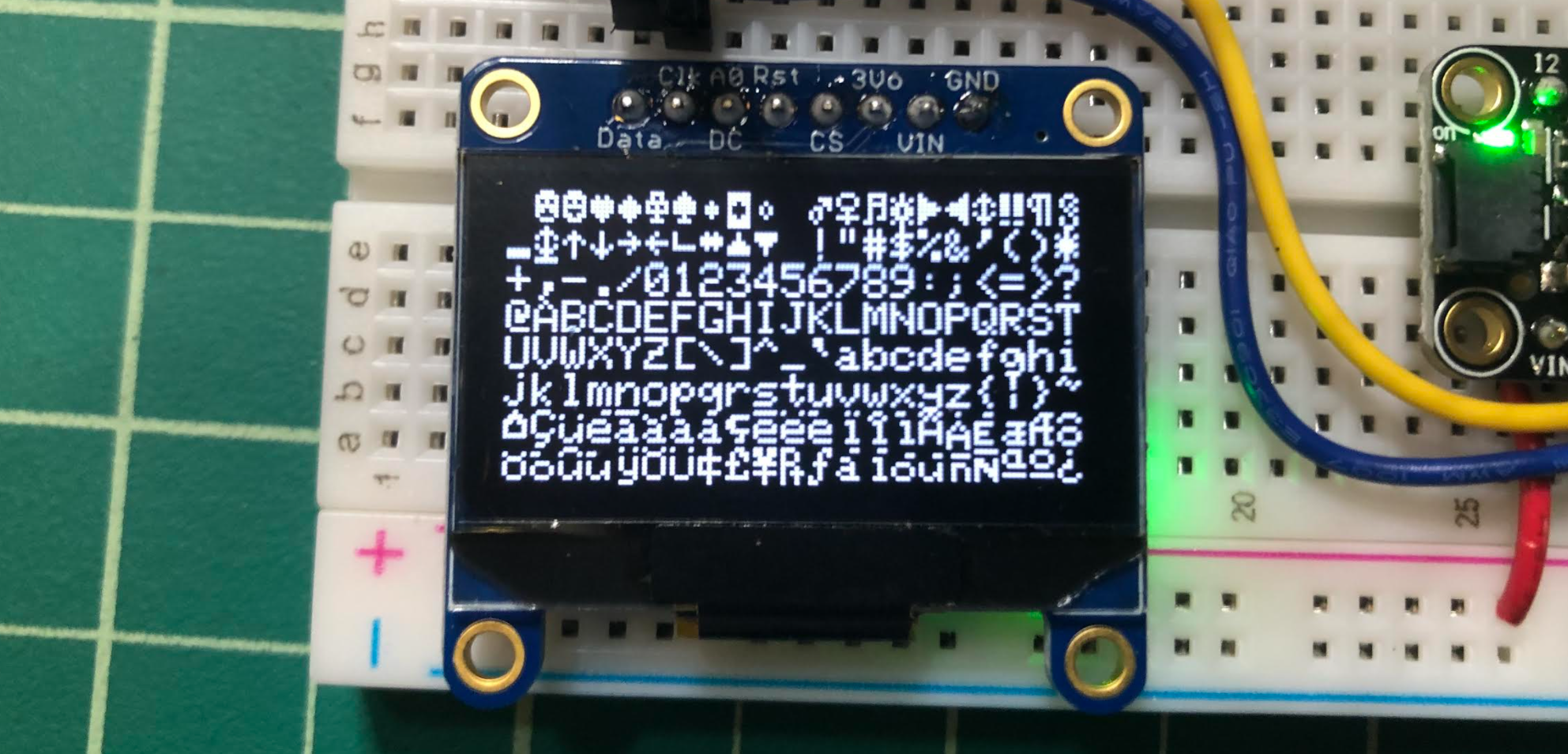

Drawing the embedded font graphics

You can draw the embedded font graphics either using drawChar or, similar to Serial.write(), the Adafruit GFX library also supports the write() function.

While you can also use either drawChar or write, the latter uses the currently set setText parameters like setTextSize and setTextColor—which is helpful. Below, I’m printing out all of the glyphs embedded in the default font, which includes embedded graphics like smiley faces, hearts, spades, etc.

Figure. Drawing the embedded glyphs in the default font using

Figure. Drawing the embedded glyphs in the default font using _display.write(). This code is called DrawAllChars.ino in our GitHub.

To draw a happy face—which is char index 2 in the middle of the screen, for example, we could use drawChar:

const int CHAR_WIDTH = 5;

const int CHAR_HEIGHT = 8;

int charSize = 3;

int charWidth = charSize * CHAR_WIDTH;

int charHeight = charSize * CHAR_WIDTH;

int charIndex = 2; // for smiley face

uint16_t yText = _display.height() / 2 - charHeight / 2;

uint16_t xText = _display.width() / 2 - charWidth / 2;

_display.drawChar(xText, yText, (char)charIndex, SSD1306_WHITE, SSD1306_BLACK, charSize);Or we could also use the write() method:

int16_t x1, y1;

uint16_t textWidth, textHeight;

int charIndex = 2; // for smiley face

_display.setTextSize(3);

_display.getTextBounds("X", 0, 0, &x1, &y1, &textWidth, &textHeight);

uint16_t yText = _display.height() / 2 - textHeight / 2;

uint16_t xText = _display.width() / 2 - textWidth / 2;

_display.setCursor(xText, yText);

_display.write(charIndex);Here’s an example iterating through all of the glyphs individually, which demonstrates the code above. Again, you can use either drawChar or write and I demonstrate both in DrawChar.ino

Video A demonstration of DrawChar.ino showing how to draw the embedded graphics from the default font.

Loading custom fonts

In addition to the default fixed-size, mono-spaced font, you can also load and render an alternative font. See the “Loading Fonts” section of the Adafruit GFX tutorial.

You can also make your own font or custom symbols for your font. See the Adafruit tutorial: “Creating Custom Symbol Fonts for Adafruit GFX Library”.

Drawing bitmaps

Finally, you can load and render custom bitmaps on the display. See “Displaying Bitmaps” on Last Minute Engineers.

Adafruit GFX Resources

Before moving forward, we strongly encourage you to read the official Adafruit GFX tutorial and the “Last Minute Engineers” OLED tutorial—both offer great overviews of the Adafruit GFX library and how to display text, draw shapes, and load and display bitmaps.

In addition, you can:

-

View the Adafruit GFX library source code here, including the Adafruit_GFX.h, which shows the available API. Yes, depending on your familiarity with C++ and reading .h files, this might be intimidating or overwhelming—but it’s important to demystify these libraries. They are just source code that devs wrote. And, with experience, you could too!

-

Examine our own OLED examples here, including the Hello World example mentioned above, a simple animation example called BallBounce, an object-oriented version of this animation using the Shape.hpp class from the Makeability Lab Arduino library, and simple games such as a collision test, Pong, and Flappy Bird. We’ll go over some of these below.

Let’s make stuff!

In this part of the lesson, we are going to make a variety of OLED-based creations. This should be fun! As mentioned, we have a GitHub repo of OLED examples, some of which we describe below.

Activity: draw shapes and text

First, to get a feel for and experience with the Adafruit GFX API and the coordinate system, let’s simply draw some text and shapes to the screen. You get to choose what you want you want to draw and where. Think of it like abstract shape art!

Remember, in loop(), you need to:

// Clear the display. If we don't do this, we'll simply be drawing over our

// previous renderings (which you may sometimes want but generally not)

_display.clearDisplay();

// Put in drawing routines

drawStuff();

// Render graphics buffer to screen

_display.display();I made a version, called SimpleDrawingDemo.ino that draws shapes of random sizes and locations on each frame but you could do something even simpler (or more complex)!

Video A demonstration of SimpleDrawingDemo.ino.

Shape drawing prototyping journal activity

For your prototyping journals, create your own shape/text drawing demo. Take a picture or, if there is animation, record a short video or animated gif. In your journals, link to the code, insert the pictures/videos, and reflect on what you learned.

Activity: draw a bouncing ball

Now that we’ve gained some familiarity with the drawing API and graphics pipeline, let’s learn a bit about animation.

We are going to draw a simple bouncing ball around the screen. Bouncing or reflecting objects are one of the key components of many games, including Pong, Arkanoid, etc.

To create a bouncing ball, we need to:

- Track the x,y location of the ball across frames

- Set a x,y speed in pixels per frame—that is, how much the does the ball move per frame? For smoother animation, we could track x,y speed in terms of time (e.g., pixels/second); however, this is slightly more complicated (e.g., it requires tracking timestamps in the code, computing time deltas, etc.). For our purposes, tracking x,y speed in terms of pixels/frame is fine.

- Check for collisions when the ball collides with the ceiling, floor, or walls of the screen. When a collision occurs, simply reverse the direction of the ball.

- Draw the circle at the given x,y location.

Prototyping ideas with p5js

Here’s a demo of a bouncing ball we made in p5js. Sometimes, it’s useful to prototype a visualization or game idea in a rapid programming environment like p5js or Processing before coding it up in C++ for Arduino (and it’s easier to debug in those environments as well). You can edit and play with this demo in your browser here using the p5js online editor.

Video. A video of the Ball Bounce demo created in p5js. You can edit the source code and run it live in the p5js online editor here. Alternatively, you can view the source in our p5js GitHub repo.

C++ implementation using Adafruit GFX

For the C++ implementation using the Adafruit GFX library and Arduino, the key bits of code are excerpted below. The overall implementation is quite similar to the p5js version. Make sure you read over this code carefully and understand it.

Again, rather than, say “miles per hour” or “pixels per second”, we’ve defined speed as “pixels per frame”—that is, how many pixels does the object move per frame. If we set _xSpeed to 5 and _ySpeed to 0, then the ball would move 5 x pixels per frame (and simply bounce back and forth from the left side of the screen to the right and back again).

// Create the display object

Adafruit_SSD1306 _display(128, 64, &Wire, 4);

// Ball global variables

const int _ballRadius = 5;

int _xBall = 0; // x location of the ball

int _yBall = 0; // y location of the ball

int _xSpeed = 0; // x speed of ball (in pixels per frame)

int _ySpeed = 0; // y speed of ball (in pixels per frame)

void setup() {

// Initialize the display

_display.begin(SSD1306_SWITCHCAPVCC, 0x3D)

// Gets a random long between min and max - 1

// https://www.arduino.cc/reference/en/language/functions/random-numbers/random/

_xSpeed = random(1, 4);

_ySpeed = random(1, 4);

}

void loop() {

// Clear the display

_display.clearDisplay();

// Update ball based on speed location

_xBall += _xSpeed;

_yBall += _ySpeed;

// Check for ball bounce. First check for going off left or right side of screen

if(_xBall - _ballRadius <= 0 || _xBall + _ballRadius >= _display.width()){

_xSpeed = _xSpeed * -1; // reverse x direction

}

// Now check for bouncing on floor or ceiling

if(_yBall - _ballRadius <= 0 || _yBall + _ballRadius >= _display.height()){

_ySpeed = _ySpeed * -1; // reverse y direction

}

// Draw circle

_display.drawCircle(_xBall, _yBall, _ballRadius, SSD1306_WHITE);

// Render buffer to screen

_display.display();

}You can view the full code on GitHub as BallBounce.ino.

Bitmap bounce

We also have a similar “bounce” demo, called BitmapBounce.ino, that uses a bitmap rather than a graphic primitive. To create the the bitmap byte dump, we used this image2cpp tool on this Makeability Lab logo.

Video. A video of BitmapBounce.ino.

Animation prototyping journal activity

For your prototyping journals, create a custom animation demo, record a short video or animated gif, link to the code, and reflect on what you learned. As one simple example, change the object bouncing around from a circle to a rectangle. If you want something more challenging, try bouncing a triangle around the screen and using the entry angle and triangle angles to properly calculate the reflection (it’s probably easiest to do this using vector calculations). Or you could use the drawLine method to animate rain fall similar to this Purple Rain video by the Coding Train. While this was made for p5js, it would fairly straightforward to translate to Arduino and the Adafruit GFX library.

Activity: interactive graphics

Finally, for our last activity, let’s make a few interactive prototypes—that is, graphics that respond to digital or analog input. Interactivity captures the true essence of physical computing. And for an HCI professor like me, this is where the joy really begins!

Demo 1: Setting ball size based on analog input

We’ll start with changing a shape’s size based on sensor input. While you can use whatever sensor you want, for this demonstration, we will use our ole trusty potentiometer hooked up to A0.

The OLED + pot circuit

Here’s the circuit. Same as before but we’ve added a 10K potentiometer.

Figure A basic OLED circuit with potentiometer input on

Figure A basic OLED circuit with potentiometer input on A0.

The OLED + pot code

The code is simple: read the analog input and use this to set the circle’s radius.

void loop() {

// On each loop, we'll want to clear the display so we're not writing over

// previously drawn data

_display.clearDisplay();

// Read the analog input value

int sensorVal = analogRead(ANALOG_INPUT_PIN);

// The maximum radius is either the display width or height, whichever is smallest

int maxRadius = min(_display.width(), _display.height());

// Now calculate the radius based on the sensor val

int radius = map(sensorVal, 0, MAX_ANALOG_INPUT, 0, maxRadius);

// Center the circle

int xCircle = _display.width() / 2;

int yCircle = _display.height() / 2;

// Draw it on the screen

_display.fillCircle(xCircle, yCircle, radius, SSD1306_WHITE);

// Render the graphics buffer to screen

_display.display();

delay(50);

}You can view the full code on GitHub as AnalogBallSize.ino.

Video. A video of AnalogBallSize.ino.

Demo 2: Setting ball location based on analog input

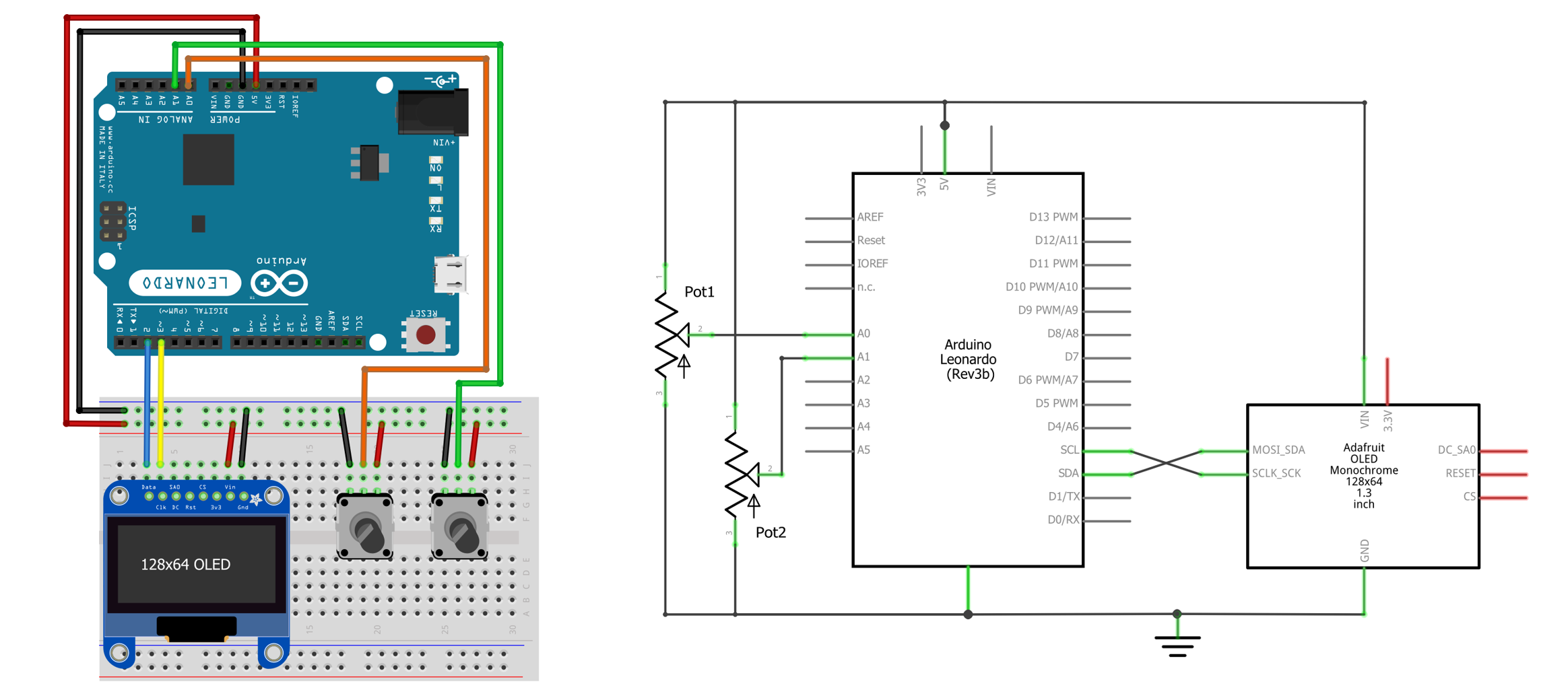

Now let’s hook up two analog inputs to control the x,y location of the circle rather than the size. In this case, we’ll use two potentiometers. The wiring diagram is below.

Figure The wiring and circuit diagram for two potentiometers and the OLED display.

Figure The wiring and circuit diagram for two potentiometers and the OLED display.

For the code, it’s very similar to AnalogBallSize.ino. But we translate the analogRead values to x and y locations:

void loop() {

// On each loop, we'll want to clear the display so we're not writing over

// previously drawn data

_display.clearDisplay();

// Read the analog input value

int xSensorVal = analogRead(X_ANALOG_INPUT_PIN);

delay(1); // give ADC time

int ySensorVal = analogRead(Y_ANALOG_INPUT_PIN);

// Translate sensor readings to x, y pixel locations

int xLoc = map(xSensorVal, 0, MAX_ANALOG_INPUT, 0, _display.width());

int yLoc = map(ySensorVal, 0, MAX_ANALOG_INPUT, 0, _display.height());

// Draw it on the screen

_display.fillCircle(xLoc, yLoc, BALL_RADIUS, SSD1306_WHITE);

// Render the graphics buffer to screen

_display.display();

delay(50);

}You can view the full code on GitHub as AnalogBallLocation.ino.

Video A demonstration of AnalogBallLocation.ino using potentiometers on A0 and A1.

Demo 3: Basic real-time analog graph

One of the most famous Arduino + Processing demos is the real-time analog sensor graph (link): the Arduino reads sensor data using analogRead then transmits it to the computer using Serial.println() where it is parsed and graphed using Processing.

With the OLED display and the Adafruit GFX library, we can easily recreate this entirely on the Arduino!

The idea is simple: read in a sensor value as sensorVal, draw a vertical line at xPos of a length proportional to sensorVal, increment xPos, repeat. When xPos >= _display.width(), set xPos back to zero, clear the display, and start the whole process over.

Notably, this code takes advantage of selectively calling _display.clearDisplay(). Unlike the other examples we’ve shared thus far—which clear the display on each frame—here, we take advantage of graphics persisting across _display.display() calls to “build up” our graph over time. That is, we only draw one new line per new sensor input, which persists on the screen until _xPos >= _display.width() at which point we call _display.clearDisplay().

void loop() {

// Read the analog voltage value

int analogVal = analogRead(ANALOG_INPUT_PIN);

// Draw the line for the given sensor value

int lineHeight = map(analogVal, MIN_ANALOG_INPUT, MAX_ANALOG_INPUT, 0, _graphHeight);

int yPos = _display.height() - lineHeight;

// For purely horizontal or vertical lines, there are optimized line-drawing

// functions that avoid costly angular calculations

_display.drawFastVLine(_xPos++, yPos, lineHeight, SSD1306_WHITE);

_display.display();

// If the x-position of is off the right side of the screen, clear the display

// and start the graph over

if (_xPos >= _display.width()) {

_xPos = 0;

_display.clearDisplay();

}

delay(10);

}The full source code is available in our OLED GitHub as AnalogGraph.ino. Here’s a video demo:

Video A demonstration of AnalogGraph.ino using a potentiometer for analog input on A0. We also show the currently sensed A0 value in the upper-left corner and our frame rate (fps) in the upper-right corner.

Demo 4: Real-time scrolling analog graph

A slightly improved but more complicated version of the analog graph is a scrolling implementation. Rather than clearing the display when xPos >= _display.width(), we simply “scroll” the content to the left. For memory and computational efficiency, we implement this with a circular buffer, which is the size of our screen width (so, 64 values—one for each x pixel).

Look over the code. Does it make sense?

int _circularBuffer[SCREEN_WIDTH]; //fast way to store values

int _curWriteIndex = 0; // tracks where we are in the circular buffer

void loop() {

// Clear the display on each frame. We draw the entire graph on each frame

// from the _circularBuffer

_display.clearDisplay();

// Read and store the analog data into a circular buffer

int analogVal = analogRead(ANALOG_INPUT_PIN);

Serial.println(analogVal);

_circularBuffer[_curWriteIndex++] = analogVal;

// Set the circular buffer index back to zero when it reaches the

// right of the screen

if(_curWriteIndex >= _display.width()){

_curWriteIndex = 0;

}

// Draw the line graph based on data in _circularBuffer

int xPos = 0;

for (int i = _curWriteIndex; i < _display.width(); i++){

int analogVal = _circularBuffer[i];

drawLine(xPos, analogVal);

xPos++;

}

for(int i = 0; i < _curWriteIndex; i++){

int analogVal = _circularBuffer[i];

drawLine(xPos, analogVal);

xPos++;;

}

_display.display();

delay(10);

}The full source code is available in our OLED GitHub as AnalogGraphScrolling.ino. Here’s a video demo.

Video A demonstration of AnalogGraphScrolling.ino using a potentiometer for analog input on A0. We also show the currently sensed A0 value in the upper-left corner and our frame rate (fps) in the upper-right corner.

Which graph version do you prefer? AnalogGraph.ino or AnalogGraphScrolling.ino? We personally prefer the latter!

Interactive graphics prototyping journal activity

For your prototyping journals, rapidly prototype an interactive OLED demo using a sensor of your own choosing and a design a simple visualization or responsive graphic around that input. In your journal, include a brief description with short video (or animated gif) and reflect on what you learned. As one simple idea to give you an idea of what we’re looking for here, how about combine animation + interactivity: what if you changed the ball speed in BallBounce.ino based on sensed input?

Resources

OLED

-

OLED Display Arduino Tutorial, Last Minute Engineers

-

Monochrome OLED Breakouts, Adafruit

-

Adafruit_GFX Library, Adafruit

-

SSD1306 Datasheet, Solomon Systech

-

Fast SSD1306 OLED Drawing with I2C Bit Banging, Larry Bank (video demo)

Serial communication protocols

Next Lesson

In the next lesson, we will learn about vibration motors and how to use them with Arduino.